Change

South Africa. Round 2. Learning how to change the world.

11th December 2017I’m sitting in Heathrow Airport, London waiting on the last of three flights home to West Belfast from South Africa. So, I’m going to type a few words to pass the time and help me digest ten inspirational days spent with activists driving international movements for social change.

What do you write to do justice to an adventure story with characters like Desmond Tutu, Bernadette Mc Aliskey, Opal Tometi (co-founder #BlackLivesMatter) and Craig Dwyer (social media strategist supporting the recent ‘YES’ marriage equality votes in Ireland and Australia)?

What words explain the lives and struggles of Zahra and Yashar, two Syrians working on statelessness and supporting refugees in the battle to open European borders, closed by the very same governments whose foreign and domestic policies drive millions from their homes in the first place?

What do you write to respect Brad, Phumeza, Dustin, Mazibuko, Zelda and Phumi? Generations of activists steeped in decades of South African struggle for human dignity. Now organising new leaders for better health, equal education, basic sanitation, community safety and adequate housing, in conditions not witnessed in Ireland since An Gorta Mór, yet widespread across the global South.

And they are just a few in the first class to come through the Social Change Initiative fellowship program. There is a wealth of experience to tap from this group of people embedded across a spectrum of struggles.

It would be time well spent to forget this blog right now and travel via the links and wonders of the web to get insights from Irūngū Houghton from Kenya to learn about the recent Red Card electoral campaign, Alice Mogwe from Botswana to learn about the African Value of Botho, Charlene Carruthers from Chicago to learn how the Black Youth Project 100 are responding to a ‘Justice’ system that murdered Trayvon Martin and released his killer.

And, Soket Soni from India, America and the rest of world. I hope he doesn’t mind me laughing again at how often he got lost in a small camp which couldn’t have been more than half a square mile in size! Somehow this lack of spatial awareness operates in perfect harmony with a towering intellect which has helped organise the New Orleans Workers Centre for Racial Justice in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. In the twelve years since Hurricane Katrina, Soket has helped build a further 60+ such centres all over the United States of America.

Or check out Stephanie Leonard, inspired by her Nanny Leonard to change her own world, and then the worlds of others with Citizen Uk. Stephanie has now developed a free, web based toolkit for activism – actbuildchange.comGo raibh míle maith agaibh Stephanie agus Nanny Leonard.

Stephanie reminded us in the process that hoarding information and knowledge is as bad as hoarding resources. No one has all the answers. Just share what you know with humility, ask for nothing in return and hope that it blossoms into something beautiful.

This meeting of minds, worlds, skills and experience which I can’t do justice to in a blog happened because of other, less visible but no less impressive activists leading the Social Change Initiative, redistributing wealth to all of us. They know who they are and don’t seem to like praise so I’ll not mention or thank Martin, Eleanor, Padraic and Sarah and everyone else on the ground in Boschendahl and Belfast ; )

For me it’s been a privilege and inspiration. Marissa Mc Mahon and I were given the resources to travel the world to harvest knowledge from cutting edge activists in various fields of struggle. Marissa’s trip started 9 years ago as she and baby Luighseach faced eviction from the New lodge Tower Blocks in North Belfast. I was piggybacking on Marissa’s activism and hundreds of homeless families who built the #EqualityCan’tWait #BuildHomesNow campaign. They use PPR’s human rights based community organising model to change their world – conceived in 2001 by Inez Mc Cormack. She and others were frustrated by the lack of delivery of human rights promises in the British – Irish peace process and the failure of the so-called Celtic Tiger Economy and ‘social partnership’ to deliver equality.

We have now made friends across continents who saturated us in principles, tactics, structures and strategies for change. We witnessed victories, defeats, savage violence and deep humanity in equal measure. We found immediate practical application of the learning to our own struggles in Ireland and plan to share everything as soon as our tech savvy comrades at the Creative Workers Co-Operative show us how.

But, I can’t write about social change without mentioning what needs to change. Like Inez Mc Cormack always said – we need to name the problem before we can address it.

So, I need to name the systemic, widespread denial of human dignity that prevails in South Africa, replicated across the global south to facilitate the privilege of the global north. Death and destruction greasing the wheels of a global, neoliberal political and economic machine, which is destroying our world. But that’s abstract and academic and does little justice to real life.

Better to explain the story of Abahlali BaseMjondolo – a shack dwellers movement born in Durban, now organising at least 42,000 shack dwellers across South Africa. A movement of ‘free’ South Africans – beneficiaries of the freedom struggle and Anti Apartheid Movement – now discarded by the state, handed a food parcel every five years by the African National Congrass (ANC) when they want their ‘black vote’.

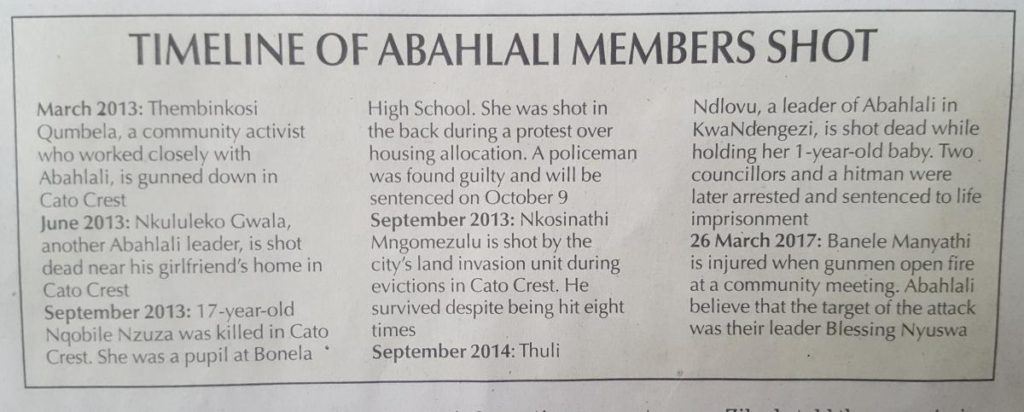

Abahlali are being shot off the streets for daring to question the status quo. They are building new power outside and beyond South Africa’s failed political and economic structures.

For the last three days of my trip, Thapelo, Abahlali’s General Secretary, opened up his home and the movement, allowing me a short dip in the waters of Ubuhlalism – a concept of democracy deeper and more transcendental than any variety of progressive politics or ‘socialism’ I’ve witnessed, where ‘my neighbours burden is my burden’ and ‘my neighbours hunger is my hunger’.

I was privileged to attend the monthly assembly, a cacophony of political discussion, song, sorrow and energy. I listened to Thapelo translate speeches from men and women, young and old, totally confident in themselves and their growing movement. I stole the opportunity to send a photo back to An Dream Dearg. (Thank’s Whitney from Cornell!)

Abahlali are known as the ‘red shirts’. Thapelo was more than happy to send some solidarity across continents to the young ‘red shirts’ back in Ireland campaigning for Acht Gaeilge (An Irish Language Act – legislative protection for the language, culture, and way of life of the Irish population living in the North of Ireland), obstructed for 20 years by political parties with the acquiescence of successive British and Irish Governments. Now the cause of the latest collapse of the Stormont ‘power sharing’ political institutions.

The failure to deliver Acht Gaeilge is another broken promise of the 20 year old Good Friday Agreement. It was supposed to afford a basic level of state respect to people like me and my kids, Gaelgeoirí. In areas like west Belfast, an Dream Dearg have become a lightning rod for all of the other broken promises of equality harnessing a widespread disillusionment with the political process. The circle of an Dream Dearg on a back drop of Abahlali activists tells a million tales of solidarity and struggle.

It was humbling to the core to be invited in by these dynamic activists, telling stories that would make even those who survived the violence of war in Ireland recoil in terror. And yet, they have questions and the humility and wisdom to know that they don’t know everything. Inquisitive about the young people of An Dream Dearg and the families of the Equality Can’t Wait campaign – a world away suffering another colonial hangover, yet as dignified and determined to move beyond our failed political process to build a better world.

On my last day we headed to court to claim back some bail money for Thapelo’s comrades arrested for ‘public violence’ and released without charge. Thapelo shrugged off the cycle of state repression of Abahlali protestors with a smile.

He then brought me back to his place. An informal settlement of 1,000 people on the side of a hill in Durban, nestled between some very rich people and a motorway. They first occupied a disused ruin of breezeblocks years ago. A cop ‘owns’ the land and property and many other properties in the area. I was reminded of the multimillionaire who owns Hillview Retail Park in North Belfast – allowed to make a mint from public funds and government policies whilst denying much needed resources to homeless families.

Since the settlement began they have built a community of people forced to migrate from all over Africa. They have built their own childcare facilities, sewerage and sanitation facilities, electricity and water supplies, commerce and entertainment. And when the state, at the request of the cop, responded with violence and court action, they organised a resistance which has inspired thousands and secured and strengthened the community in the process.

So, after a few days there was nothing left to do but go for a beer and a game of pool in the local bar – a hut with a pool table and some form of ingenious music sound system, plumbing and electricity. Beers emerged from a magical door out the back.

We had great craic, not least because of my fine performance on the pool table. It was life affirming to laugh with new friends and share beer on the side of a hill in South Africa in a thriving self organised, participative democracy, built on what looks from the outside to be a rubbish tip.

Then I was racked with guilt and the certainty of my own privilege in the north, built as it is on the misery of the south.

I asked Thapelo what we can do of practical use and he gave me a few pointers. I made my promise as he reminded me I was about to miss my flight home.

We sped through Durban in a taxi, just like the black taxis on the Falls Road – transport shared by various people heading in more or less the same direction. Moving at light speed I was no longer worried I would miss my plane. I struggled not get depressed with the the big questions raised the previous week in our activist camp in Boschendahl.

How do we move beyond the limitations and inherent failings of representative democracies and economies of the present where money flies across borders in seconds yet people are caged forever? How do we democratise wealth, not just politics? How do we organise effective lasting movements for global change, not just temporary localised life rafts?

Thapelo and millions of others the world over are already grappling practically with, and surviving amidst, these contradictions. Tomes of analysis have been written by thinkers and academics. Scientists, doctors, engineers and tech experts have designed solutions with a million applications. And every society has activists speaking to the contradictions of our world which benefits so few at the expense of so many.

Yet, these many and varied life rafts for humanity are disconnected and people keep returning to service the sinking ship. Sometimes, as a South African comrade reminded me, we even throw stones in other people’s life rafts. Why do we keep building a boat that will sink us all? – think Zuma, Trump, May, Guptas, Goldman Sacchs, Elizabeth Windsor. Why do we lend them our power?

But Thapelo and Abahalali refuse to keep building the old world that binds them and are instead building a new world – it is not without pain and suffering and faces massive odds. But if shack dwellers in South Africa can build a society from nothing and defend and expand it in the face of such brutal force, inspiring comrades from other struggles new and old in the process, then anything is possible.

We know the problem. The answers are there. The ways and means are plentiful. Na h’abair é, déan é. (Don’t say it, do it)